POLITICS: Republican rising stars Mike Pence and Mark Sanford are making all the right enemies by Russ Pulliam, Warren Smith

With moderates John McCain and Rudy Giuliani the talk of media towns, conservatives are on the lookout for new faces. Here are two: U.S. Rep. Mike Pence of Indiana and Gov. Mark Sanford of South Carolina.

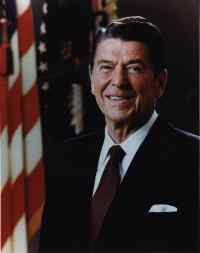

Mr. Pence, a 46-year-old Republican, is getting attention as an advocate of a leaner federal government who also has good credentials as a cultural conservative. He has an instinctive grasp of the news cycle from years of talk-radio show hosting in his home state. He is gaining mention as a possible future speaker of the House, with Rep. Dennis Hastert (R-Ill.) likely to step down in 2008.

Yet Mr. Pence's Christian faith and past struggles with political ambition make him uncomfortable about pursuing higher political aspirations at the expense of family (wife and three young children), or just to satisfy natural human desires for fame and adulation.

Lately he has pushed the Bush administration and the Republicans in Congress to take some air out of the ballooning federal deficit. He and his conservative bloc in the House, the Republican Study Committee, forced the House leadership to reduce federal spending boosts for rebuilding after Hurricane Katrina. Mr. Pence appeals to both evangelicals and the business-oriented wing of the Republican Party: Business Week recently called him a "self-effacing Hoosier as comfortable quoting Scripture as the Contract with America."

His optimistic disposition also is fueling this rise to prominence after just five years in the House. "I'm a conservative, but I'm not in a bad mood about it," he likes to say: "There is a tendency among some conservatives to communicate as if they have been sucking on lemons."

Mr. Pence has a strong pro-life record and has displayed support for faith-based initiatives. When the Bush administration was trying to figure out how to get federal grants to faith-based groups, he joined with other members of Congress in suggesting the simpler approach of tax credits so that citizens could send money right to the charity of their choice. "When I give $1,000 to a rescue mission, I've probably given four times [more] than if I sent the money to the bureaucracy in Washington," he says. "It actually reaches the homeless man and pays for a meal for him."

With his mix of social and economic issues, he is showing the capability for uniting Republicans in a way that took Ronald Reagan to the presidency. While the Giulianis and McCains appeal to economic conservatives, the key to GOP leadership, as Ronald Reagan and George W. Bush have shown, is appealing to both wings of the party.

That combo attracts favorable comment from unlikely quarters, such as the New York Times editorial page. He proposed a federal shield law to protect news reporters from having to reveal their sources in criminal investigations. If that makes conservatives nervous, he notes that his position is essentially conservative, helping to keep some checks on government. "The role of the press is to create that accountability for people who wield public power," he says.

All this favorable attention might go to a congressman's head, but he was chastened a few years ago about the raw pursuit of political success and tries to remember the lesson. After his unsuccessful 1988 and 1990 campaigns for Congress, he wrote an essay, "Confessions of a Negative Campaigner." Then he became a popular talk-radio show host before his election to the House in 2000. "I developed a very healthy skepticism of my ambition 15 years ago," he said. "There is a tendency when you are in a public position to begin to think more highly of yourself than you ought to."

Bible reading, along with going home to his wife Karen and three children, 13, 12, and 11, helps keep him humble: "When I walk into the house, I'm no longer the congressman or the conservative leader. "I'm just Dad."

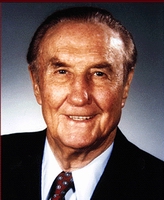

South Carolina Governor Mark Sanford, 45, is one year younger than Mr. Pence and has four children. He excelled in athletics and academics as a young man, made a fortune as an investment banker, and was elected to Congress in the pivotal "Republican Revolution" year of 1994, a year made famous by the Contract with America, which promised a smaller, more accountable federal government.

Mr. Sanford showed his own fiscal restraint—and a shrewd understanding of the power of symbolic action—by sleeping in his Washington office and showering in the congressional members' locker room. But the most significant symbol of his tenure in Congress was that he kept a campaign promise to serve only three terms. He stunned everyone (except those who knew him) by leaving his "safe seat" after six years, and not just to run for something else, but to return home to his 3,000-acre farm near Beaufort and enjoy his growing family.

Then Mr. Sanford did something that doesn't get mentioned much in his official biographies: Already in his 40s, at a time when many career military personnel are retiring, he joined the Air Force Reserves. Asked, "What in the world were you thinking?" he laughed and said, "My wife asked me that, too." Then he answered seriously that as a member of the International Relations Committee, he often traveled with military escorts: "I would end up on an aircraft carrier in the Persian Gulf or with troops in Germany. I just became profoundly impressed with the United States military."

Mr. Sanford also said he came to believe that we had "disconnected the rights that go with being an American from [the] responsibilities that go with being an American." He said he wanted his four boys to know they had a responsibility to serve, and he wanted to lead his boys with his example, not just his words.

Leading by example, and striking the right chord with words, image, and action—these are hallmarks of Mr. Sanford's record as a public servant. One of his first official acts as governor was to go to Orangeburg, S.C., and apologize to a mostly black audience for the infamous Orangeburg Massacre, a nasty incident of racial hatred that had long been a blight on the state's history. When he wanted to cut state spending, he exercised the line-item veto more than 100 times on the state budget, but the legislature overrode most of his vetoes, so he brought two pigs into the rotunda of the state capitol in Columbia to make the point that there was too much pork in the budget.

South Carolina House Speaker David Wilkins called the pig stunt "childish" and "insulting," and the state's liberal media delighted in Mr. Wilkins' outrage, saying it proved that the governor couldn't even get along with fellow Republicans. But Mr. Sanford had the last laugh, or squeal: He managed to keep spending growth to 1 percent, cut the state's budget deficit by more than 90 percent, and saw most of his revolutionary 16-point reform package passed.

What Time magazine called the governor's "conspicuous frugality" underlay its recent designation of him as one of the three worst governors in the country. But the American Conservative Union has honored him as the "most conservative" governor in America, while the Wilkins-led House of Representatives gained Citizens Against Government Waste's badge of shame as "Porker of the Month" for June 2004.

Mr. Sanford replied to the newsweekly's designation by saying, "I have read Time; I will still read Time. They may be left-leaning, but it's good to check in with what the left is thinking." He continues to push for using the tax code to effect social change, with his proposed "Put Parents in Charge Act" as a prime example: Under it, South Carolina residents could claim tax credits for private-school tuition, homeschooling expenses, or contributions to scholarship-granting organizations.

Good Mood Conservatives